How do we get stuff done?

#campcrafting 004: The role of prosocial governance in overcoming challenges

We want the principles to guide the creation of shared social practices that help groups dynamically balance individual and collective interests. We want groups to function so that individuals can be authentic and free but exist within strong, caring groups that leverage their effectiveness and meet their social needs.

~Atkins, Wilson, and Hayes

1. Camp Governance

One of the most central questions any cohesive group has to answer is: how do we get stuff done?

While writing I had been searching for works that could assist groups in overcoming challenges. There was an abundance of literature on the topic, and I found myself overwhelmed. Crucially, none were grounded in the applied evolutionary science I was hoping to find, until in 2019 a book written by Paul Atkins, David Sloan Wilson, and Steven Hayes: Prosocial: Using evolutionary science to build productive, equitable, and collaborative groups.1 My camp now has three, well worn copies. This article serves as a campcrafting geared outline of the core prosocial principles you can explore deeply at Prosocial World.

2. The Atlantean Origin Story

Along our campcrafting quest, The Atlanteans2 have overcome some significant challenges to our living within an intentional community. To date, we are thriving. But, it was not a foregone conclusion that we would make it. In fact, within the first year of collective existence, we suffered major financial and emotional setbacks, with job loss during the pandemic and a member divorcing both the camp and her spouse. Let me list just a few of the challenges we had at the onset of our journey:

We lived in different countries, and had different passports.

We had jobs with varying degrees of remote work capacity.

One of our members found out she had become pregnant.

One of our members was unemployed.

One of our members was getting a graduate degree.

We had varying levels of conceptual “buy in” from the group, ranging from “all in” to deeply skeptical.

Some of these challenges every group will have, others will be unique to the suite of pressures each person brings to the group. Let’s take one of the aforementioned Atlantean challenges — varying levels of commitment to the campcrafting quest. Specifically, one member was especially skeptical of the project. To date, even through the loss of a member, we’ve sustained and grown through all these challenges. There were certain tools that were critical to us overcoming adversity, and in this article we’ll focus on one such tool — Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Matrix — to foster psychological flexibility in individuals and groups. In a following section, you’ll get a nice video describing the process.

For context, it’s worth delving a bit into our camp journey to illustrate where the tool came into use.

At the onset of the Pandemic, the nexus of the group composed of four guys (Bear, Wolf, Lion, and Stag) with relationships in duration that sum over five decades of friendship. We decided to finally execute on the campcrafting quest. Three of the guys were pairbonded to three of the gals, Bear to Horse, Wolf to Peacock, and Lion to Turtle. In essence, it was up to the tightly bonded guys to pitch the idea to the loosely bonded gals and see if we could, as a party, venture forth. We all knew each other to varying degrees, had spent some holidays and partied together, but nothing close to sharing a prolonged living space.

After several group conversations, consensus built around the idea. Things happened quickly after that, with some focus and planning, we got to the task of finding a home. The raw energy of the group to try our hands at campcrafting propelled us to signing a multi-lease mortgage on a home. It was a huge commitment by all, which involved two marriages, a new child, several moves, new jobs, feeling out remote work options, and a massive financial commitment for those on the mortgage and heaps of trust on those who weren’t.

Peacock and Wolf lived in the region where we were to co-locate, and they accepted the responsibility of the lionshare of the legwork involved in finding a home suitable for cohabitation. Videoconferencing in on home visitations, the rest of the camp gave input, but once Peacock found a home she loved, we all jumped at the chance to do what we could to close the deal and begin the quest.

Morale was high. For the guys, it was a dream come true. Literally, for Bear and Wolf, the idea had been in fetal stages for well over a decade. Coming in, the ‘to do’ list was immense: moving, setting up, designing, cocreating public spaces, figuring out weekly and monthly chores — when just living together would have been totally novel. Lion was in between jobs, and so Bear and Wolf subsidized his monthly mortgage until he would eventually land an exciting, career launching job. Stag lived remotely, but was a de facto member and leader of the real estate company the guys had built for half a decade, and that was contributing towards the mortgage. Turtle had just graduated and was working on her Masters degree. Turtle, on the very first night in our cohabitating camp, announced she was pregnant — and it was a surprise to everyone, even Lion! The sheer amount of what we had accomplished so quickly had garnered momentum at our back and a lot of energy put into the pot.

But things quickly got weird…mainly for one person — Peacock. Due to being pairbonded to Wolf, that weirdness extended soon to two people. And when two people are grappling with existential questions, the impact is palpable and immediately has an effect on camp psyche. After the first week, Peacock (in secret meetings with the other Mortgage holders) voiced concerns. The issues ranged from concerns of freeloading (because of the unemployed members) to general concerns about tightness of public spaces. This was the first of many, and I mean many meetings. In all, over the several month period by which we found our governance style, there were several hundred meetings. Sometimes between pairs, sometimes between three or four or five members, or in many, and most critically, between all members. It was hard, human work.

What we did not know at the time (I had yet to come across the primal template of Tight versus Loose culture to be discussed in a later article) was Peacock was a statistical outlier when it came to tightness. Briefly, cultures have different strictness in their social norms. Tight cultures have strong social norms that are clearly defined and strictly enforced. Loose cultures have weak social norms that are more flexible and informal. Tight cultures are found in societies that are uncomfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. Loose cultures are found in societies that are more comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. This prime culture template can be measured in the individual and in groups of any size34. So a group a three people can average individual scores and determine their tight versus loose scores.

Our camp mean for Tight-Loose culture was an average of 64. Peacock was a 98! And to add spice to the curry, she was also just recently married to Wolf, who was the outlier in the other direction being the loosest of our camp. She had a very specific vision for how her home would operate, and deviations were incredibly stressful for her — which directly impacted Wolf — and indirectly impacted the lived experience of every member in the group.

Without the benefit of the terminology, the primal template for culture, we somewhat blindly navigated the churning political waters of the camp. Much of the core scientifically supporting strategies that I researched during this “field season” were critical in the stabilization of a struggling camp, and they involved finer points on best practices for negotiations, determining camp roles, and establishing and enforcing social norms. Fortunately, this is explored in great detail in OUR TRIBAL FUTURE: How to Channel Our Fundamental Instincts Into a Force for Good. I highly recommend referring to it as a resource for your camp. But one resource in particular proved to be the foundation of what became our governance strategy…

3. The Prosocial Bible

The word ‘prosocial’ is a worldview oriented towards the welfare of others. The central issue in governance is: what are the best practices for a group to get the best of each other and achieve their goals while mitigating conflict and overcoming adversity? In other words, how do we create a prosocial culture that raises the wellness bar for everybody committed to the campcrafting quest?

To this end, the most powerful tool we’ll use — and one of the ways The Atlanteans overcame their challenges — is the ACT Matrix. It helps your camp to develop and act on its collective consciousness with purpose. It is a tool designed to help people identify and map their interests, build psychological flexibility, and set goals within a scientific framework that can be measured over time. Here is a step-by-step guide to help facilitators measure the culture of their camp and how to assess some key design principles for effectively working together. In the attempt to streamline the process, I’ve crafted a Campcrafting Assessment Survey that will email you your responses so that you can calculate your group averages for each category as well as derive a total sum (out of 60) as a general index for camp health.

The key component we’ll highlight here is the development of psychological flexibility within your camp.

The primary aim is to explore what motivates your group members and learning some techniques for managing some challenges of cooperation. Once you knock out these surveys, you can engage the ACT Matrix first individually, and then as a team. As promised, here is a video outlining the process. It’s great if the whole camp wants to watch the video, but I certainly didn’t task my camp to do so. As the facilitator, I read up on the science Core Design Principles5 and the ACT Matrix and led my group through the process.

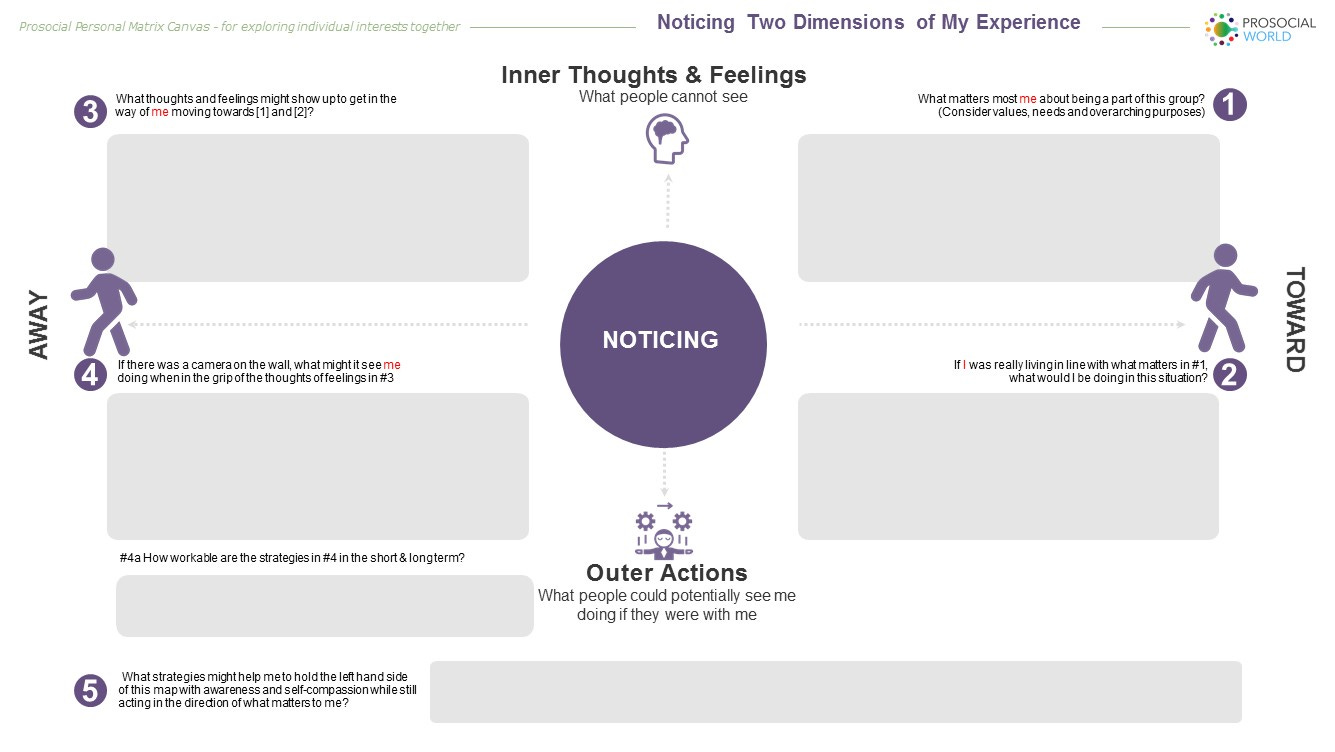

All animals are motivated to approach what they want more of and avoid what they want less. Breaking down this figure, human motivation comes in two varieties. The first kind is getting more of what we want (e.g., money, power, world peace) and the second kind is avoiding and having less of what we don’t want (physical pain, social ostracization, failure). Think of these two kinds of motivation as either moving 'toward' what matters or 'away' from what we dislike. This dimension is represented in the below figure by the horizontal line in the center of the matrix, with a little guy (on the left) moving away, and the little guy (on the right) moving toward.

The other key dimension — represented by the vertical line in the center of the above matrix — is the distinction between the internal mental world (moving down) and the external world (moving up) of the senses. Because we can use language, humans are a bit different than most species of animals. This gives us the unique capacity to plan for the future and recall the past. When we combine both dimensions — moving toward and moving away with the experiences of the mind and the senses — we create a two-by-two matrix consisting of four distinct quadrants. In the top right quadrant 1 you have the internal values that motivate you to identify and share purpose with your camp. In the bottom right quadrant 2 you have the behavioral out actions that you perform when they are in alignment with such values. In the top left quadrant 3, you have the thoughts and feelings that disrupt or get in the way of both 1 & 2, and in the bottom left quadrant 4 you have the actions you exhibit when you are acting out those disruptive thoughts and feelings.

An important step is mapping out your own motivation to be a member of a camp, which can be done by using the Individual Matrix. Go ahead and fill it out.

Now that you’ve got a grasp on personal motivation, it’s time to begin mapping collective motivation! If individual interests can be facilitated by collective purpose, this step will find common ground to help. As a camp, come together with the help of a facilitator and discuss your responses from the Individual Matrix. Then use this discussion as a launching point for the creation of a Collective Matrix.

4. The Atlanteans get Prosocial

If a group is to achieve any of their goals, and create anything of value, they need to be able to efficiently and effectively make decisions.

When it comes to the core design principle of fair and inclusive decision making, one of the golden rules is: if it affects someone then they need to be included in the decision.

Thus, a critical decision-making venue, your group’s legislative body, is the camp meeting. As a camp we committed to a weekly meeting. We designated a sacralized space, after our Sunday evening feast, to ritualistically come together, eat, share the week’s joys and burdens and talk campcrafting. This was space that would ultimately function to facilitate the most important group decisions for goal setting and reflection on progress towards these goals.

But its first task was to assess where we were as a camp. To establish a baseline we delved into a discussion about the Prosocial Core Design Principles. This theory won the economist Elenore Ostrem a Nobel Prize for solving the tragedy of the commons problem. Here, it’s scaled down to help your camp, as it did ours, when our aim was to determine where we needed to focus our energy, and help guide our next actions as a group. Below is a figure that visualizes the Core Design Principles. Ignore 7 & 8, as they pertain to how groups interact with groups, and we’re just focused now on your camp. For your camp’s needs, it may be helpful to do what we did and make a google survey with a 1-10 scale for spoke’s 1-6. You can revisit this annually or semi-annually to get a grasp on your camp’s progress, or lack thereof. Just as a wheel needs all its spokes to function well, groups need these principles to be strong, resilient, and sustaining.

When we graded ourselves at this early stage we identified several areas we could target for improvement, but none more so than the arguably the most important dimension — camp identity and purpose. We scored a dismal 4.2! We had work to do, and much of the outline of that work is featured in the next article on forging cohesion. To this end, we each filled out our Individual Matrix, and in a subsequent camp meeting came together to craft our Collective Matrix. This was when we came up with the following for mapping our internal values that motivated us being members of the camp.

Listing these values was key to what, in the future, would be our agreed upon sacred values to embolden camp identity and purpose. We then described what kind of actions we would have if acting in accordance with these values:

This list gave us actionable goals to consider and aim towards. We then considered internal thoughts, and how they might interfere with 1 & 2.

All these were fears each member had, and it was remarkable recounting them to each other as we noted many of us shared the same fears. We then considered how these internal thoughts influenced our behaviors in unproductive ways.

We realized, if we were to become a true camp, we shouldn’t let these thoughts materialize into behavior. With respect to addressing Peacock’s concerns, specifically the maintenance and organization of shared public spaces in the home, we committed to doubling down on efforts to tighten up these domains.

We leveraged communication technologies, by way of apps such as WhatsApp and Signal to facilitate group communication. We utilized the polling and voting options for decision making. These are great for day-to-day check-ins on tasks, but cannot replace a formal space for which to meet and discuss camp priorities and goals — so we religiously kept to the camp meetings each Sunday. A quarterly meeting was set up to establish several higher-order, more strategic objectives that link the work of the entire team and push forward the long-term purpose of the group. Every six to twelve months, we would set big strategic meetings to update and reflect upon group purpose, ultimately guided the next iteration of goals to be set for the group.

The guiding concept for the monitoring of agreed behaviors is accountability. One obvious way to make behaviors transparent is by sharing their progress with the group; this is easily facilitated with project management tools such as Trello or Asana. A visual record, shared by all members is a great way to implement effective monitoring. There are several benefits to monitoring, as people act more prosocial when they know people are watching. This is known as a reputation protective behavior that enhances motivation and increases shared identity, improves coordination, and decreases cheating.

Although, monitoring can go wrong when it deviates from the purpose of the group and it’s done coercively. To ensure this doesn’t happen, it’s always good to frame monitoring in the light of support — not control. For example, when Turtle and Lion had their baby, the kitchen food-preparation hearth became overcrowded with baby nipples, bottles, sterilizing machines, bibs, and the like. To keep the domain tight, but also show some compassion for the new mom and dad, instead of direct confrontation for failure of maintaining a tight domain, a more powerful yet indirect tactic we employed as a group was to ask if they needed any help with the task. This way, they were reminded of the importance of the task, but instead of feeling policed they felt supported. Typically, that’s enough to ensure people double down on the task and if they do ask for your help, in good faith, they likely needed it.

As a camp, we were upping our game. And, we could feel it. Yet, all the while, the more we seemed to improve cohesion, the more stress Peacock experienced. Months of couples therapy with Wolf did not prove a salve either. The more our purpose and identity as a group coalesced, the more Peacock distanced herself from the camp. After a full eighteen months of engagement, Wolf and Peacock divorced, and she left the camp. Wolf lived true to his values and so did Peacock. It’s only that the former’s values were the camp values and the latter’s were not. Fascinating, something interesting had happened along the way. The Atlantean identity had come into its own. The group has overcome its first major existential threat, and through it leaned into each other as a source of strength. The camp was stronger than ever.

5. Unfurl the Sails

It’s helpful on the outset to calibrate realistic expectations. In the quest to build a greater intentional community, you may extend and push the boundaries of your Honor Group by bringing in individuals that may not ultimately be compatible with your group. In our case, Peacock’s high Tightness scores, among other personality differences relative to the group, proved intractable. The challenges may fracture some ties, and create new ones, as with all social and environmental challenges. The sociologist Nicholas Christakis in his book Blueprint:

“Friendships begin and end. But the overall social organization of the species stays the same. Some turnover in social ties within groups may even be necessary for the networks to endure. It’s like replacing planks in a boat. This is required to keep the boat seaworthy. But the plan of the boat, like the topology of the social network, remains fixed, even if all the individual boards are eventually replaced.”6

In other words, we had lost a plank to the boat, but it remained not only afloat, but with wind in sail.

It is likely why the quest for intentional community is one of the oldest and most continued in our species history; from the first camps to the cohousing communities of the 21st century, humans — as long as we are humans — will never stop trying to live together. Your camp will create a shared consciousness and a unique culture. And by channeling the prosocial drives within, you and your campmates will build a boat of your own and sail to lands of your choosing. Unfurl the sails — may the wind be at your back!

Now it’s time to finally get to the really dynamic stuff. We’re about to harness the ancient magics of human ritual to embolden our #camcrafting quest. We’ll explore this topic in the next article.

Thanks for reading The Tribe Drive ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Atkins, Paul WB, David Sloan Wilson, and Steven C. Hayes. Prosocial: Using evolutionary science to build productive, equitable, and collaborative groups. New Harbinger Publications, 2019.

Some background on why we chose this moniker will be provided in the following article on camp cohesion

Gelfand, Michele J., et al. "Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study." science 332.6033 (2011): 1100-1104.

Harrington, Jesse R., and Michele J. Gelfand. "Tightness–looseness across the 50 united states." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111.22 (2014): 7990-7995.

Wilson, David Sloan, Elinor Ostrom, and Michael E. Cox. "Generalizing the core design principles for the efficacy of groups." Journal of economic behavior & organization 90 (2013): S21-S32.

Christakis, Nicholas A. Blueprint: The evolutionary origins of a good society. Hachette UK, 2019.

I wonder what you think of this: Paul R Ehrlich, Daniel T Blumstein, The Great Mismatch, BioScience, Volume 68, Issue 11, November 2018, Pages 844–846, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biy110

I wonder whether you find that lack of supportive community affects movement levels and quality? This is something that can be measured with a great deal of granularity.