Building a DIY Village

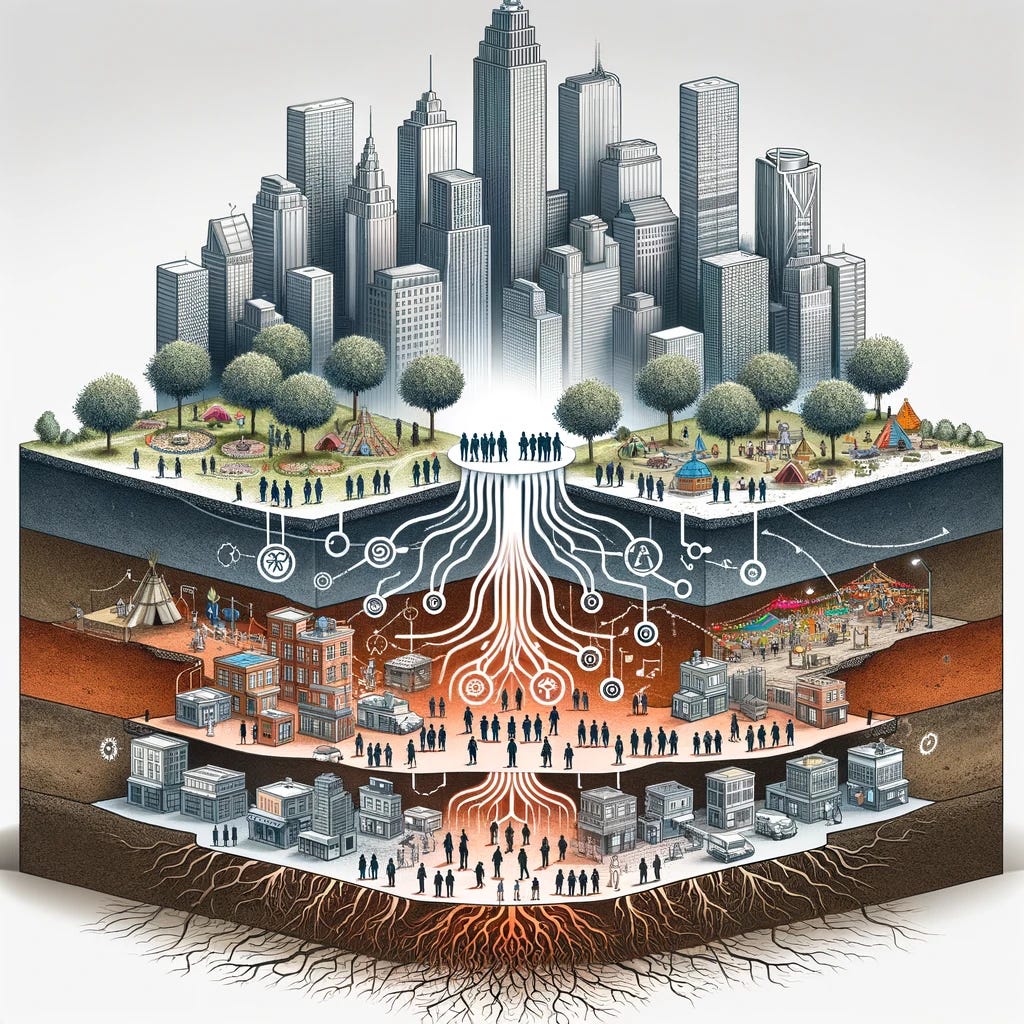

#tribaltheory004: Using the Tribe Drive to Scale Intentional Communities of the Future

Building a society without understanding the science of group size is like scaling a ship without knowing the fundamentals of ship design. Take the infamous Swedish warship, the Vasa, commissioned by King Gustav Adolf in the 1620s. The king demanded a ship 30% larger and equipped with extra heavy artillery. The shipbuilders, lacking knowledge of scaling, failed to account for the design's complexities. The Vasa was too top-heavy and capsized on its maiden voyage, a tragic loss before it even left Stockholm harbor.

For centuries, we’ve expanded cities and groups intuitively, relying on trial and error rather than a scientific approach, that takes into account evolutionary anthropology, to scaling human communities. Just as with the Vasa, even a small error in understanding how a group should scale can lead to disaster.

For 99% of human evolutionary history, Paleolithic tribes rarely exceeded 5000 people, a size where social cohesion could be maintained naturally. This is hardwired into our social biology, making the complexity of modern cities a new challenge for human society. If we don’t understand the principles of scaling, that scientists like Geoffrey West1 have identify, we risk repeating the mistakes of the past.

West’s demonstrates that cities grow through superlinear scaling: Y = Y₀N^β (where Y represents a given property like economic output, N is population size, and β is the scaling exponent, typically greater than 1).

This equation reveals that as cities grow, both the benefits and costs scale disproportionately. Without integrating social structures that align with human cognition, cities will face amplified risks that can ultimately lead to social fragmentation. In short, ignoring the balance between ancient group dynamics and modern scaling laws will doom our efforts to build the thriving, cohesive cities of the future.

Luckily, today as our legacy systems show their wear and tear, we have tools like Dunbar’s number2 and Christakis’ Social Suite3 to prevent social calamity. These insights provide a solid framework to build stable communities by respecting the natural limits of human social connections. The emergence of this true social science is perfectly timed — as movements like Srinavasan’s The Network State4 — and many others are driving efforts to build new kinds of societies across North America and beyond.

Foundation

Behind every successful society, there were founders. Every new society starts with a core group. For Rome, (apocryphally) it was Romulus and Remus, but in reality it was likely a kind of Honor Group of 3-5 trusted individuals. This group is the foundation, much like the hull of a ship. These individuals should embody the vision and values of your new start-up society. Just as the leadership of a startup forms its heart, your Honor Group will set the tone, make key decisions, and ensure the initial stability of your project.

Rituals and Roles are crucial. To strengthen bonds and establish authority, create distinct rituals or symbols for your Honor Group. This might include ceremonial roles, titles, or even physical symbols of leadership, like rings or badges. Honor Group leadership will be critical in guiding the first expansion.

From the Honor Group, we move to the next rung of the Dunbarian scale, the Sympathy Group, which typically includes about 15 people—forming the core leadership of your initial Block. I've explored this process, which I refer to as 'campcrafting,' in several articles in the applied section of the Substack. It’s a rewarding and demanding endeavor that not only builds your social health but also transforms you personally. We’ll skip its details here and head to the genesis Block.

The Genesis Block

Once your core leadership is established, the next step is to expand into a block. Going back to the middle ages, this would be a hamlet, which might consist of a cluster of houses, perhaps with a few other buildings like a small shop, a community hall, or a central commons, in this era likely a place of worship. There's often no central planning or grid; buildings might be scattered or loosely grouped. Going back even further, in Paleolithic terms, this a cohesive unit of 30-50 people called a “camp.” In the parlance of modern day city planning this would be termed a precinct. A precinct is like a small town block, self-sustaining and internally well-connected.

Within each block, break people into sub-groups or Honor Groups of 3-5 individuals for specific functions—whether it’s governance, resource management, or events. These decision making nodes create efficient, small-scale groups, ensuring that no one feels lost in the larger structure. This system mirrors ancient social structures, where smaller units were essential for maintaining order and productivity.

In a block of this size, group identity and rituals are crucial to your societies cultural development. Rituals like anniversaries, communal meals, and festivals reinforce the shared identity of the group. Create initiation rites for newcomers, and emphasize selective membership, ensuring that everyone contributes meaningfully to the community.

Welcome to the Neighborhood

As your village grows, you’ll eventually scale to a neighborhood of up to 150 people. Dunbar’s number suggests that 150 is the maximum group size where stable personal relationships can be maintained. In Paleolithic terms, this is the nested group of local camps that creates a band. Beyond that, it becomes difficult to sustain cohesion and unity because after scaling beyond the band you’re dealing with strangers. Each neighborhood should consist of 3-5 blocks. While each precinct operates autonomously in day-to-day life, the neighborhood provides a shared sense of identity and purpose. Create leadership councils to oversee larger projects and keep communication clear between each block.

Sodality is a powerful tool at this level. A sodality is a club, where individuals rally behind specific goals or passions that contribute to the larger whole, are great for heading events that solidify the group’s identity and public projects that bring everyone together and remind them of their shared mission. When the United States had it’s incredibly high levels of post-WWII social cohesion, small towns of 1500 people often times had dozens or more active thriving sodalities sponsoring tribe wide events. These events act like the rigging and sails of a ship, keeping the entire structure bound together and able to navigate the complexity of growth.

The Village People

You’ve finally formed a true intentional community at scale when you’ve made it to the village. The U.S. Census Bureau might categorize places with populations below 2,500 as rural villages, which in a city would be classified as a district. At the district level, you’ll be managing up to a maximum of 5000 people. As paleolithic tribes are typically 1500-5000 people, the district is equivalent to a “tribe”, a collection of bands or “neighborhoods” that maintain their unique identities but are united under a larger governance structure and powerful unifying symbols.

A district is made up of nested group of 10-30 neighborhoods. While neighborhoods retain autonomy, the district council will oversee governance, large-scale infrastructure, and major economic initiatives. This structure prevents chaos by dividing responsibilities across multiple layers of leadership.

Maintaining unity in a district of 5000 requires large-scale festivals, community projects, and cross-neighborhood collaboration. The events help reinforce collective identity and cross-neighborhood collaboration and, with the use of the identity symbol that represents your district, helps keep scaling cohesion.

To Cities, States, and Beyond

The Roseto effect5 reminds us that human wellbeing thrives at the village scale, where close-knit communities mitigate the challenges of superlinear city growth. If you design a city with the village as its core tribal unit, you’ll create a place worth living in—a city that promotes health, cohesion, and resilience. By leveraging Dunbar’s numbers and Christakis’ Social Suite, you can create balanced growth, where tightly bonded neighborhoods scale into cohesive districts. This maximizes local autonomy while bolstering a super-ordinate identity that keeps the whole acting in concert. This strategic approach will not only ensure your city's stability but also foster a vibrant, unified culture that can weather the complexities — and inherent chaos — of exponential growth. In the end, building a city that thrives isn’t just about expanding—it’s about creating a place where people feel connected, supported, and inspired to grow together. With the right foundation, your city can be a beacon of resilience, where progress and community flourish hand in hand.

West, Geoffrey. Scale: The universal laws of life, growth, and death in organisms, cities, and companies. Penguin, 2017.

Camilleri, Tracey, Samantha Rockey, and Robin Dunbar. The social brain: The psychology of successful groups. Random House, 2023.

Christakis, Nicholas A. Blueprint: The evolutionary origins of a good society. Hachette UK, 2019.

https://thenetworkstate.com/

The Roseto effect refers to the phenomenon where a close-knit community, like that of Roseto, Pennsylvania, experienced significantly lower rates of heart disease compared to surrounding areas during the mid-20th century. Despite having diets high in fat and engaging in unhealthy habits like smoking, the tight social bonds, communal living, and low levels of stress contributed to their improved heart health. Studies found that as the community became more assimilated and lost its traditional social structure, heart disease rates increased to match the national average. This shows how social cohesion and stress reduction play critical roles in public health outcomes.